By Dr. Warren Brown, May 2020

Please see the article below written by Warren Brown on the impact of the new COVID-19 debt on South Africa.

The short version of this article was published on page 6 in the 29/05/2020 print edition of Business Day.

Click here if you would like to read the short published version. Alternatively, continue reading below for the full article.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In a speech as recent as October 2019 (Medium Term Budget Policy Statement 2019) Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said the following regarding South Africa’s growing debt service costs: The consequences of not acting now would be gravely negative for South Africa. “Over time, the country would likely face mounting debt service costs and higher interest rates and may enter a debt trap.”1 Debt service cost is the interest paid on a country’s debt – the greater the debt, the greater the service costs.

These words were spoken before the additional COVID-19 related R500bn package was announced. SA’s debt as a percentage of GDP was 62% in 2019 and the IMF projects it to grow to 77% in 2020.2 Moody’s ratings agency says that 2019’s figure is higher at 69% if one includes guarantees to SOEs, rather than 62%. 3

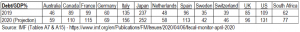

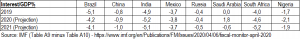

Table 1: Public debt as a percentage of GDP

Table 1 shows that South Africa is not alone in the level of accumulated debt with several other “Advanced Economies” sitting with (relatively) more debt to pay off.

Compared with other alternatives of raising public financial resources, public indebtedness is not usually considered to affect monetary stability of a country adversely. This is because it mostly involves redistribution of existing resources in the economy.4 Besides, governments can accumulate debt and simply roll it over on to the next generation of the population to sort out.

One may be tempted to think that public debt accumulation sounds like it’s “okay” and that South Africans should not be as worried, as Finance Minister Tito Mboweni may suggest. However, apparently, that is not so. There are consequences to a country’s debt accumulation.

Consequences of too much debt

In early April 2020, Moody’s pushed Argentina’s rating deeper into junk territory due to deteriorating debt issues. 5 The IMF indicates Argentina’s debt as a percentage of GDP for 2019 as 89% – there is no projection for 2020. The debt servicing costs are above 13% of GDP for the next 5 years, assuming GDP stays at current levels.

In March 2020, Moody’s downgraded South Africa to below investment grade status. Moody’s rationale for the downgrade included the “inexorable rise in government debt” and warned that further downgrades would occur if it concluded that “… any combination of weak growth, failure to reduce the primary deficit, and rising financing costs was likely to cause the debt burden to rise to higher levels than currently projected …”. 3

One major consequence of a ratings downgrade is that it becomes more expensive to raise further debt. Paying more for debt increases the amount of the debt burden, and so the deterioration continues.

Debt servicing

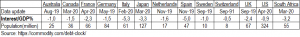

Table 2 compares the burden of South Africa’s debt servicing costs for 2019 (excluding the R500bn COVID-19 package) to other “Advanced Countries”. Since the debt structure for each country is a relatively complex issue, calculating the interest due on the debt is not a quick exercise. Table 2 simply approximates the interest due on the outstanding debt by using the interest rate on the 10-year bond for each country – it’s a rough and ready method.

Table 2: Debt interest as a percentage of GDP

The amount of interest paid on outstanding debt (debt servicing cost) is more important in sparking a financial crisis than the Debt/GDP ratio. One study suggests that if the debt servicing cost ratio rises above 5%, this may spark a financial crisis if expectations are that the level will remain above that 5% level and continue to rise. 6

Table 2 shows that South Africa’s debt servicing cost as a proportion of GDP is at 3,2%, below the 5% hurdle suggested above, but in line with other struggling EU countries such as Spain and Italy (excluding Japan for reasons not discussed here).

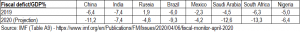

Another indicator confirming the growing debt burden is the increase in the budget deficit as a result of increased government borrowing and spending. The projected deficit as a percentage of GDP for 2020 of 13,3% will be the largest ever for South Africa with the previous largest of 11,6% in 1914. 7 This projection looks worse than those for other selected Emerging Market and Middle-Income Economies shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP for selected Emerging Market and MI Economies

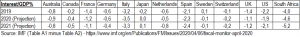

The fiscal deficit is the sum of the primary deficit and the interest payments. Using data from the IMF, we can refine the numbers shown in Table 2. Tables 4 and 5 shows debt servicing costs as a percentage of GDP across countries using data from the IMF’s Fiscal Monitor, April 2020.8

Table 4: Interest as a percentage of GDP for selected Advanced Economies

Table 5: Interest as a percentage of GDP for selected Emerging Market and MI Economies

Notably, SA’s projected servicing cost for 2021 is the worst, as compared to those for the selected countries with interest as a proportion of GDP at 5,2%.

Not all debt is bad

There are two main types of debt 9:

Self-liquidating, or productive debt, is debt spent on creating assets that are expected to generate income to pay (at least) the principal and interest due on that debt. One common type of self-liquidating debt is government investment in infrastructure.

Unproductive debt, however, is debt used for financing unproductive activities such as military spending, welfare programs and various kinds of household consumption. While unproductive debt may have a positive impact on economic welfare, it does not have a positive, direct impact on economic growth that renders the debt self-liquidating.

Debt dedicated to relieving the negative impact of COVID-19 is not self-liquidating debt.

Debt risks:

There are several ways that one government can reduce debt. 10 & 11 One way out of paying back the principal and the interest, is to default. Even if there is absolutely no intention to default on debt, the more the debt and the interest payment burden grows, the greater the potential for default. “The higher the risk of default, the higher the interest rate investors will expect: A country perceived as a higher credit risk must pay bond holders higher interest rates than a country perceived as a lower credit risk, all else equal.” 12

Another way to reduce debt that could raise serious risks is to amortise the debt value through higher inflation. Rising inflation has several associated risks, not least the destruction of savings and other aspects of economic ruin.13 Some commentators are convinced that the fiscal and monetary easing that is currently taking place will, inevitably, result in higher inflation. Professor Jeremy Siegel believes that the bond market’s 40-year bull run is coming to an end, as the tremendous liquidity build-up will fuel a steady rise in inflation. 14

What’s the plan?

There isn’t a convincing debt reduction plan that will excite investors, at least as of yet. Fortunately, since it is still early days, financial markets and rating agencies will give SA more time to present a plan, but they will reprice SA downwards in the absence of one.

A plan is needed to manage expectations, particularly as to how SA will reduce its debt and ensure that the interest payments are manageable without negatively impacting on economic growth. Rising future debt will reduce potential growth and stifle efforts to implement new policy initiatives.12 High debt levels reduce the flexibility of fiscal policy to respond to economic shocks such as the financial crisis of 2008/2009. Over-indebted governments will find it difficult to extend credible guarantees to the financial sector.15 Similarly, an over-indebted SA government would find it increasingly difficult to use moral suasion (or other) to convince investors that debt issued by State Owned Enterprises (or their proxies) would be supported by the government in cases of default.

At least one plausible argument is that the only perception that matters is that of foreign investors.16 SA needs to convince foreign holders of SA debt that it has a credible plan.

Summary and conclusion

South Africa’s Finance Minister warned that SA may be entering a debt trap prior to the recent addition of COVID-19 related debt. The recent increase in SA’s debt consists of a large amount of unproductive debt. The increasing debt (and servicing costs) will fuel perceptions that SA will not be able to manage the debt appropriately, nor the consequences of the increasing debt.

Government needs to provide investors, particularly foreign holders of SA debt, with a credible plan as to how SA will reduce its debt and manage the servicing costs, without it negatively impacting economic growth.

Notes

- https://www.gov.za/speeches/medium-term-budget-policy-statement-30-oct-2019-0000

- https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/04/17/Fiscal-Monitor-April-2020-Chapter-1-Policies-to-Support-People-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-49278

- https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-downgrades-South-Africas-ratings-to-Ba1-maintains-negative-outlook–PR_420630

- https://www.economics-sociology.eu/files/08_76_Bilan_Roman.pdf

- https://www.latinfinance.com/daily-briefs/2020/4/6/moodys-drops-argentina-deeper-into-junk-territory

- https://globalfinancialdata.com/paying-off-government-debt/

- https://www.resbank.co.za/Lists/News%20and%20Publications/Attachments/9839/Monetary%20Policy%20Review%20%E2%80%93%20April%202020.pdf

- https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/04/06/fiscal-monitor-april-2020

- https://sites.google.com/site/maeconomicsku/home/public-debt

- https://voxeu.org/article/major-public-debt-reductions-lessons-past-lessons-future

- https://www.thebalance.com/interest-on-the-national-debt-4119024

- https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/page1-econ/2019/11/01/making-sense-of-the-national-debt_SE.pdf

- https://www.resbank.co.za/AboutUs/Documents/Why%20is%20Inflation%20Bad.pdf

- https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/wharton-professor-jeremy-siegel-bond-market-bull-run-ending-inflation-2020-5-1029170679

- https://voxeu.org/article/major-public-debt-reductions-lessons-past-lessons-future

- https://www.investec.com/en_za/focus/economy/finding-our-way-out-of-the-debt-trap-demands-more-than-monetary-policy-can-offer.htm

IP Management Company (RF) Pty Ltd is the Manager of the Collective Investment Scheme. The reader acknowledges that all disclosures are available at https://www.mi-plan.co.za/disclosure/ and the Minimum Disclosure Document for the fund is read in conjunction with this article.